Adding TypeScript Codegen to a Large GraphQL Schema

David Rhoderick//15 Min Read

Adding TypeScript codegen increases the strength of your API contract and lessens the importance of unit tests, making your application both more stable and deploy more quickly. However, with large organizations and large schemas, implementing codegen after the fact can be challenging.

In a large enterprise with a years-old schema and distributed ownership, adopting codegen late is nontrivial. This article walks through both the benefits and the hard realities of doing it after the fact.

Adding TypeScript codegen increases the strength of your API contract and lessens the importance of unit tests, making your application both more stable and deploy more quickly. However, with large organizations and large schemas, implementing codegen after the fact can be challenging.

In this article, I’ll cover the following:

- Why we wanted codegen at this stage–We were writing TypeScript types in our front end based on the GraphQL schema, which was inefficient and error-prone.

- What we actually achieved–We got codegen working with some custom tooling that enabled us to use unions and fragments more effectively.

- What fought us the hardest–Schema size, poor schema organization, lack of introspection, and split repos.

- What I’d recommend to others–Simple preparatory steps like modularizing your schema and keeping dependencies reasonably up to date make codegen a one-command experience, not an ordeal.

This isn’t a “how to set up GraphQL codegen” post. It’s aimed at teams with large, existing schemas who are wondering whether adding TypeScript codegen late is worth the pain.

But first, I’d like to start with some definitions for context…

Definitions

If you already know what TypeScript, codegen, and GraphQL are, go ahead and skip to the section on implementation. Otherwise, read on for some short definitions of what we are talking about:

TypeScript

TypeScript is a programming language that transpiles to JavaScript. JavaScript is an untyped language, meaning that it doesn’t discern the difference between a variable that’s stored as a number or a piece of text (string). TypeScript adds “typing”, which means you are forced to declare whether a variable is a number or a string, for example, and what functions expect to receive and what they return.

If a variable is considered a constant number, as in unchanging, in JavaScript, you can re-assign it to a string. This is probably unintentional, yet the application will be deployable and errors will only occur at runtime, or when the code is actually running, probably for your end-users to experience the defect. With TypeScript, you will get errors during the transpilation of code to JavaScript if you try to re-assign a constant variable or if you try to change its type from number to string.

The day-to-day advantage of typing is that as you develop, IDEs and code editors like Visual Studio Code, Windsurf, and Cursor will show you hints as to what variables are and what functions expect and return. This makes development faster because you don’t need to understand the inner workings of each function; if it’s accurately named and typed, you use it without that knowledge (until it’s necessary). It enables more developers to work across an app with less deep knowledge of it, speeding up development.

GraphQL

GraphQL is a type of HTTP API that establishes a contract between the consumer, such as web, mobile, desktop, and embedded applications, and a server. The contract differs from more traditional REST APIs in that it has 2 features:

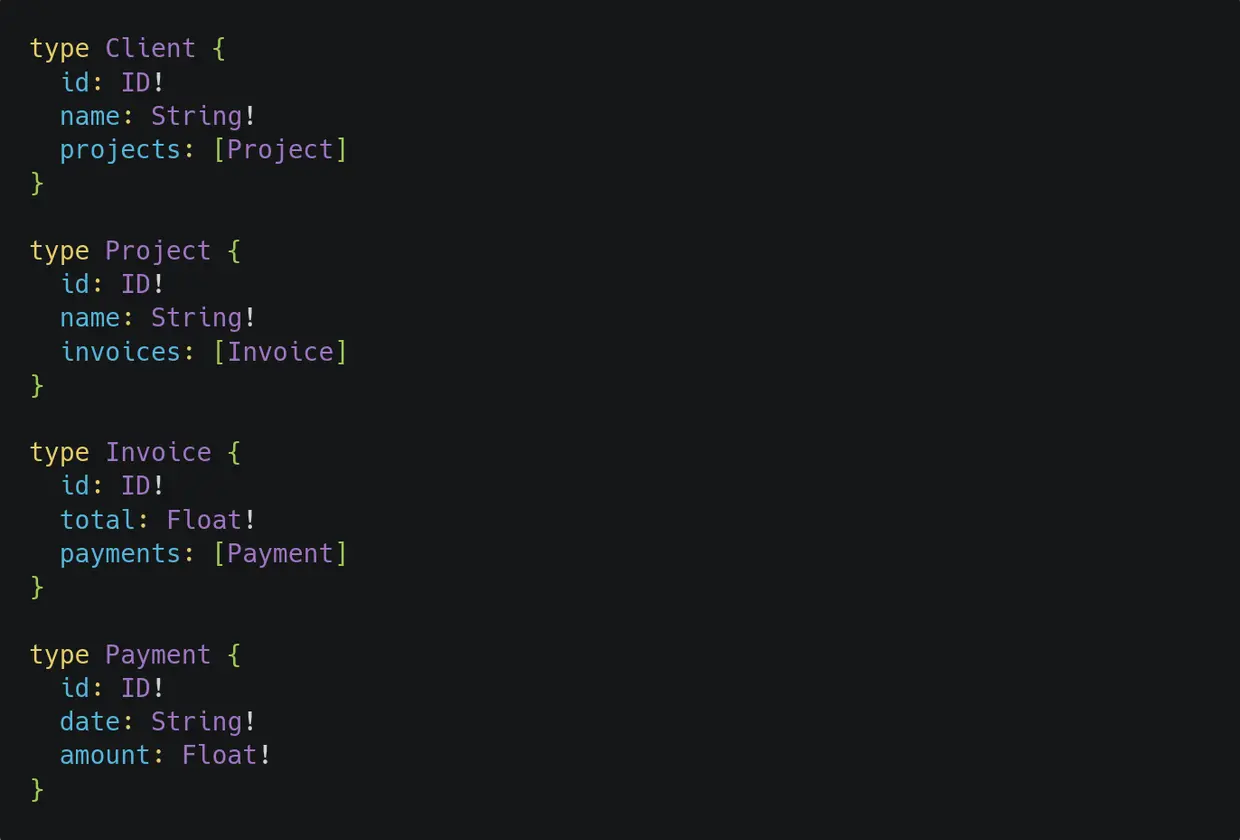

The definition of the API, called a schema, is like a “graph”, as in different objects or entities are connected together. For example, a client might have projects, which might have invoices, which might have payments. These would all be connected in the graph like the following:

Notice how the types can be referenced in other types.

Secondly, it allows you to fetch only the data you want. REST APIs typically dump all the data at once when you make a request to the server. In GraphQL, you can fetch only the data you want from each request. In combination with resolving (providing the functionality to get the data) each “field” (underneath type definitions), you can control how hard the server works from the consumer.

Codegen

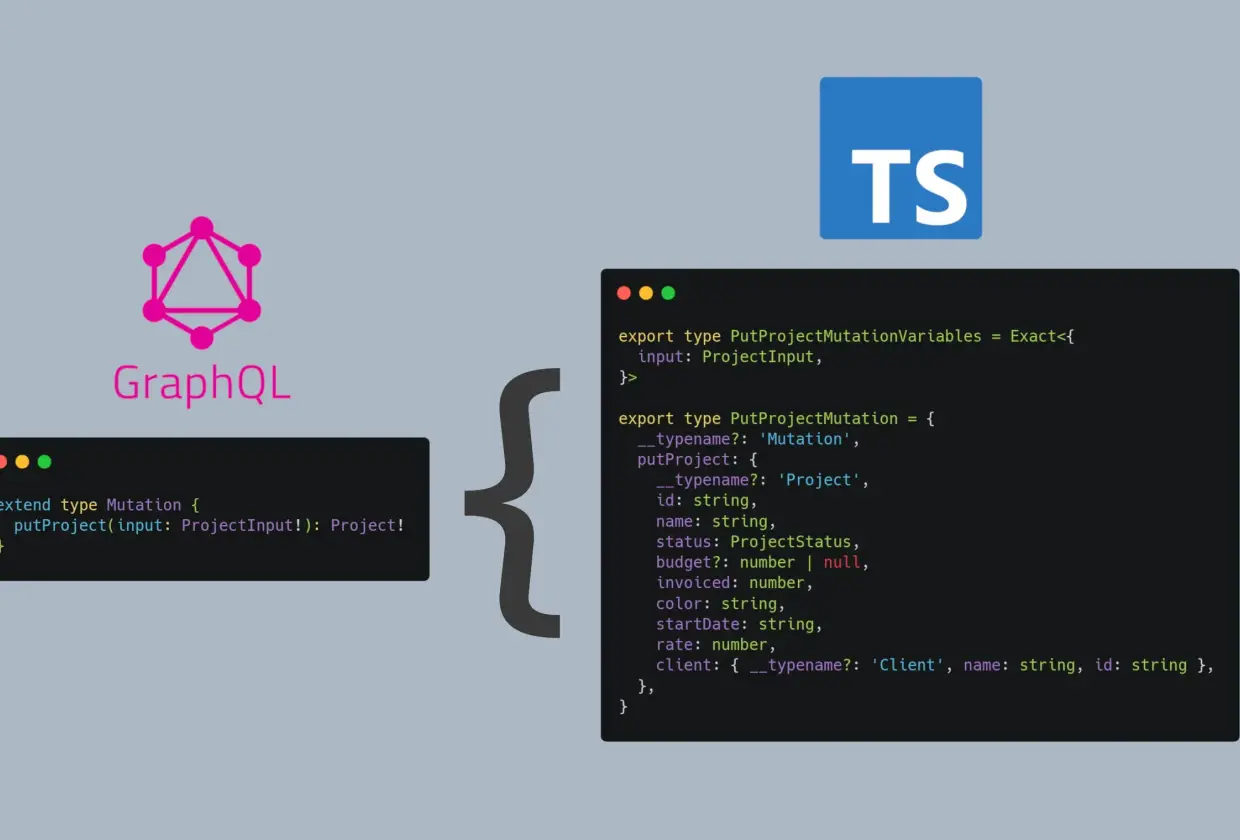

Codegen, or code generation, connects the typing of TypeScript to the schema of GraphQL. It can be run on the server-side, to enforce the schema on the code that runs to provide the data, and on the client-side, to enforce the type of the data that is returned from the server.

Without codegen, you would need to carefully define values for all the fields from the schema in the server code. In order to check this, you either write automated tests, where it’s still possible to forget to test a specific field, or to test the API itself manually, which is time consuming.

With codegen, you cannot build (transpile) your server unless all the fields you defined as required are properly resolved on the server. Optional fields can still be omitted, but that’s also OK because the schema allows it; however, those might require testing to ensure that they are indeed returned. Codegen dramatically reduces the need for low-value unit tests that just assert shapes and required fields. You still need tests for business logic, but you can lean much more on the compiler for contract correctness.

On the client side, you don’t really need to understand the schema completely. Once you have your query document, or the request you are making to the server, written, the codegen types will provide to you the shape of the data. This also helps make patterns like multiple types of returns possible; let’s say you wanted to sometimes return an error in a specific shape when success: false and the data when success: true, you can enforce this with types, catching when you are incorrectly assuming you don’t have an error. This reduces runtime errors, or errors that make it through the build and deployment of your app and only shows up when people are using it (oh no!).

Why we wanted codegen at this stage

It jumped out to me early on that writing types manually in the front end when you had a strongly typed schema was inefficient. I saw first-hand both myself and other developers misnaming fields or expecting data when a field was nullable. These were all caused by an imperfect API contract.

In talking to other developers in the program, it was widely understood that it would be good to have something like this and that manually writing types was a pain. However, the key would be not to disrupt the program at all and support both approaches, given how big the codebase and program was.

Another problem that was immediately agreed upon by developers was the lack of type safety in the GraphQL server. Nobody could answer why it wasn’t started in TypeScript and nobody seemed to know how to fix it.

Implementation

Server-side

The biggest challenge to server-side implementation of codegen is that we don’t use TypeScript here. Therefore, that upgrade was needed first:

Node upgrade

Unfortunately, the current Node version did not support adding TypeScript, so that upgrade was needed first. This is actually the most major roadblock in the process; due to wanting to avoid defects at all costs, we would require a solid testing plan or feature flag implementation. Our unit tests should catch all issues with a Node upgrade but there is still a chance something wasn’t tested fully, so that gave us around 90% certainty, which wasn’t full confidence. Feature flag usage for a dependency upgrade like Node is virtually impossible.

In a large org, technical risk is only half the story; perceived risk often matters more. Even if you believe the code is safe, if leadership isn’t comfortable with the rollback story, the upgrade won’t happen. That reality shaped a lot of what was possible here.

TypeScript implementation

Because our API server didn’t bundle, we needed to configure TypeScript to output JavaScript exactly how we currently code it. This was more trial-and-error than anything else because we had to match the style of code that hasn’t really been enforced pre-existing in the repository using TypeScript’s configuration options. However, we were able to do this.

Allowing JavaScript next to TypeScript

It is a large level-of-effort to convert all JavaScript into TypeScript and it increases the risk significantly. So in order to move forward, we had to let JavaScript remain in the codebase while we started adding TypeScript. This is a double-edged sword; on one hand, we could move forward and start implementing TypeScript. On the other hand, developers would be free to continue to write untyped code in the project.

Server-side verdict

Implementation on the server side was considered a non-starter because of the Node version and partially because of lack of bundling. While disappointing, especially in that our server consumed data from a typed server and produced for a typed front end, leaving a gap in our typing, the rate of development of this server has slowed significantly, unlike our client-side application…

Client-side

Our front end website was built in TypeScript so we already had the typing system, we just needed to generate the types from the schema. This would provide us with the following benefits:

- We wouldn’t have to manually write types in the front end based on the GraphQL schema. Not only was this task time-consuming, busy work, it was prone to errors like missing or misnaming a field, and we had no way to track duplicate types being added instead of either extended or contracted.

- We’d have less verbose code because codegen can provide either hooks or typed documents, of which we used the latter, that automatically applies types to the

useQueryanduseMutationhooks from Apollo’s client-side library instead of passing those types to those hooks. - It handles automatically union types and can help enhance caching by enforcing the typing directly on the schema. Union types are trickier to manually type and if the types and the schema misalign, it’s possible to break the cache.

However, there were some challenges:

GraphQL API and client-side code separation

First of all, the GraphQL API code was in one repository and the client-side code was in another. The API code is where the schema resides, so having this separation means we have to transport the schema to the client application somehow. Usually, one would use introspection…

No Introspection

Introspection is how the GraphQL API exposes its schema to consumers. It’s the same as a Swagger UI for REST APIs; it allows the developers to explore the API and even make requests without writing code, in the browser.

Our introspection was turned off. Therefore, we couldn’t access the schema from the client application easily. Instead, we had to solve this by sparsely cloning the API repository into the client application, focusing on the schema files, so as not to clone the entire repository, which would defeat the purpose of lessening the typing and building load on the project.

The major reason for turning off introspection is because your API is private. Why let anyone see how it works if you’re the only consumer? However, our application was generally closed to all but a small number of users, so I found it a bit limiting.

Schema size

A large schema means there are lots of types to generate. Lots of types means a larger codebase that strains the TypeScript server, which handles the IDE feedback, basically to the point of crashing, never mind the tax on building the app. Plus, it’s important to realize that we already had types for some of these types, so we were sometimes adding duplicate code that would be considered during the build but not afterwards.

The solution to the size of the schema was to create a smaller schema and incrementally use codegen. This gave us a very trimmed schema so we didn’t duplicate types. Similar to cloning the schema though, we had to add additional tooling around this to get it to work.

Schema organization

Trimming the GraphQL schema was complicated by the schema organization. All Query and Mutation definitions were in single files, respectively. That meant that you couldn’t selectively pull a query and all its types by fetching a single file, you had to fetch the entire schema or the trimmed schema would be invalid, which would prevent codegen from working.

The solution here was to properly modularize the schema, which is a practice that codegen describes in their documentation. Basically, you create empty Query and Mutation schemas, then you use the extend keyword to build on those base schemas in separate files. You keep all related schemas together in the same file so that when you fetch a schema file, you have all its dependencies.

Due to the size of the schema, this was done incrementally on a need basis and when creating new schemas. Basically, when our devs make changes to the schema or the resolvers, if they remember, they can pull out from the large Query and Mutation files what they’re changing (since you’ll be testing them as part of your review process anyway) and put them in a folder organized by use case.

For example, let’s say you have an updateClient mutation. You can create a new folder called clients and put a schema.graphql file in there. Along with adding your updateClient mutation using the extends keyword, you add all the input and output types to that file. You can also start adding the client query and deleteClient mutation, until all client functionality is in that schema.graphql file. When we filter the schema for clients/schema.graphql, we’ll get all the dependencies we need for those use cases.

So while incrementally modularizing our schema, we still had a disorganized schema overall, but what was used for codegen was starting to be organized. Now we were in a position to actually use the thing!

Adoption

While it was satisfying to set up codegen and get it working, you still needed to perform 4 steps to do it:

- Add the schemas you want to pull to the

schema-filter.jsonfile to selectively pull new schemas from the GraphQL repository. - Run the codegen sync script, which is the bash script that sparsely clones the GraphQL repo, moves the files into the project you are working on, and merges filtered files into a single schema.

- Write your query or mutation documents in a

documentsdirectory, so we didn’t have to scan the entire project for documents, again for better performance. - Then finally run the codegen.

Therefore, the results were mixed. A lot of developers preferred to continue to type things manually, especially those not working closely with our team. That’s one of the big lessons here: if codegen isn’t “boring and automatic,” adoption will be patchy. Requiring a multi-step, semi-manual sync process meant only the motivated teams really used it.

The real advantage comes when generating types for union types and fragments. Union types are when a field’s type can be one thing or another. GraphQL uses __typename to differentiate those types in the data and writing manual types for those would be complex. Using codegen and fragments, it’s easier to extract multiple types from a single field.

Conclusion

Was adding codegen this late on a success? Eh, I’m not really sure. To me, it feels like we implemented an iteration of the ideal solution rather than the full thing. Manually synchronizing filtered schema and running codegen is awkward, even if it supports everything we need to do and allows for us to have improved developer experience and application reliability. Running codegen is usually one command in a properly set up project!

However, as an iteration of the whole process, it was successful. Hopefully, we will continue to modularize our schema since it helps with organization on the whole. The next challenge is to deprecate old types and replace them with codegen alternatives. This is something that would also need to be done incrementally.

Should you use codegen?

- Are you already using typed languages? While most people are moving towards typed languages, some people are moving away. If types are not your thing, neither is codegen.

- Where are you in your application’s existence? If you start early on, you’ll be forced into better habits and by the time your codebase has become complex, you won’t even feel running extra commands to give you this security.

- How big is your schema and how is it organized? If you are starting with a large schema that isn’t modular, you are looking at an uphill battle. The payoffs are still there, but you aren’t looking at full adoption any time soon.

- How integrated are your server and application codebases? If you can make your project a monorepo, meaning you have multiple projects in one repository, codegen will be a breeze to set up. My preferred pattern is a simple NPM workspace with the front end code as the root workspace and a

serverdirectory with a nested NPM project in it. This is simple to set up and still gives you plenty of capabilities without going into more complex solutions like Nx.

I love codegen and so should you!

Maybe I was a bit partial but I believe that types are your friends. You want to offload as much cognitive load from developers as possible. The more you can hide complexity, such as what goes into a function and what comes out, the more higher-level work those developers can focus on. If you had to handwash clothing every time you changed, you wouldn’t get ready very quickly and you might even avoid changing. Avoiding codegen, in my opinion, is making extra work for yourself when, to be honest, we all already have enough on our plates.